Bordering on prison: Legitimising illegal extraction

The origins of the phrase ‘border’, which may be traced to a defend’s edge (bordeure) or the planks (bord/board) that fashioned the aspect of a ship, resonate alongside the banks of the Tapajós River within the Munduruku territory of Brazil. The sting between the Munduruku ancestral lands and the worlds of non-indigenous settlers has been travelled, transgressed and contested because the first colonial boats navigated the Amazon. It could possibly be argued that the historic remedy of the Amazon as terra nullius, devoid of individuals with distinct histories, territories and parity of rights, is reproduced in enduring Western imaginaries of pristine forests, and top-down developmentalist methods aligned to cartesian presentation of house and linear conceptions of time and progress.

On this context, the fabric borders that delineate the boundaries of the formally recognised indigenous territories in Brazil signify for the inhabitants a spatial and temporal horizon, the safety of which affords the replica of collective life, work and that means inside the forest. This text contends that for land grabbers, wildcat miners, state establishments and business organisations alike, these borders signify a legislative and geographical impediment to be reworked, reinterpreted and overcome in preparation for additional commercialisation of land and labour. This text explores the outworkings of this in relation to the border between Munduruku lands and Crepori Nationwide Forest, and the unlawful gold and ‘regulated’ timber extraction therein.

Asymmetrical temporalities on the sting of two worlds: The case of Crepori

It was amid the repression of Brazil’s navy regime that the Munduruku started expeditions in the direction of territorial defence of their sovereignty within the Nineteen Seventies. This means of territorial management within the face of ongoing authorities omission, which turned enunciated as self-demarcation from 2014 onwards, concerned successive groups monitoring and confronting invaders, mapping and demarcating their boundaries and containing land-related violence. The actions led to 2.38 million hectares being designated for his or her unique use in 2004.

The late twentieth century noticed new constitutional modifications in Brazil that assure lands and rights for Amazonian communities. It’s tough to not conclude, as does Robert Nichols nevertheless, that these territorial borders – ostensibly drawn to guard distinctive and indigenous social, financial and political actions – signify conversely ‘an unincorporated horizon’ for the relentless pressures of capitalist enlargement. As detailed beneath, the sluggish and incomplete means of formally demarcating these lands – there are not less than 850 indigenous lands that haven’t but been outlined – makes them susceptible to unlawful incursions, and contrasts sharply with the quickly launched payments that search to weaken the present authorized protections supplied by these borders.

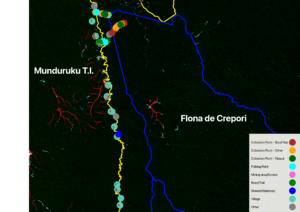

The Crepori Nationwide Forest, or ‘Flona’, with 740,661 hectares, was created in 2006, bordering the Munduruku lands (TI Munduruku), however incorporating areas traditionally and contemporarily utilized by the Munduruku folks, who weren’t consulted, in violation of ILO 169 (which requires governments to contain indigenous and tribal peoples in related laws and initiatives that may have an effect on them) and the Brazilian structure. A ‘Flona’ is a conservation space, however with a selected designation that enables the business extraction of assets inside its boundaries. The denial of the existence of indigenous occupation, subsequently, paved the way in which for the auctioning off of components of the forest. Determine 1 illustrates that neither the boundaries of indigenous lands nor the conservation space had been efficient in stopping unlawful gold mining and deforestation.

Determine 1 Map exhibiting border (in yellow) between the Munduruku Lands (TI) and Crepori Flona, and the locations of conventional use (stuffed circles) by Munduruku. These lengthen by way of to the designated Flona and inside the licensed zone for business logging concession (in blue). Areas of unlawful mining in each the indigenous land and nationwide park, 2001-2021, are proven in darkish purple.

A proper criticism in 2014 by the Munduruku paused the deliberate operations:

Our actions of fishing, searching, harvesting fruits, straw and vines are prohibited, in an space that’s our conventional territory […] the place the federal authorities created the Flona with out consulting our folks.

The irony for the unique residents is that though the logging concession was quickly suspended, the Supreme Court docket resolution that recognised the ‘affected by criminal activity’ and ‘predatory’ deforestation led to not a cancellation of the logging contracts however moderately the other: Common logging could be permitted as it will assist deal with the unlawful extraction of timber and the wildcat gold mining actions.

For the reason that licensing for regulated logging turned operational in August 2023, the enclosure of forest for logging, the noise of equipment and siltation of rivers has pressured locals to go additional to hunt, fish and collect fruit. Most notably, nevertheless, alongside the paths by way of the forest, younger males nonetheless working as unlawful miners talked overtly of pleasant relations with the staff of the timber firm that was awarded the contract.

The drone picture (Determine 2) exhibits the alarming extent of unlawful mining, seen because the ponds of deforested areas to the left of the image, that has been facilitated by the principal highway infrastructure (working south to north within the picture) constructed by the logging firm. Determine 3 qualifies the native accounts of forest loss and protracted unlawful mining because the timber concessions got here into operation.

Determine 2 A drone picture of unlawful gold mining websites adjoining to the ‘official’ highway of the timber firm, August 2025; Picture courtesy of Da’uk Munduruku audio visible collective

Determine 2 A drone picture of unlawful gold mining websites adjoining to the ‘official’ highway of the timber firm, August 2025; Picture courtesy of Da’uk Munduruku audio visible collective

Determine 3 Map exhibiting current forest loss (2022–2024) from unlawful mining (in mild blue) inside the indigenous lands and Flona. Forest loss between 2001 and 2021 is proven in darkish purple.

Determine 3 Map exhibiting current forest loss (2022–2024) from unlawful mining (in mild blue) inside the indigenous lands and Flona. Forest loss between 2001 and 2021 is proven in darkish purple.

This case is a usually unruly frontier encounter. At the moment, mining is against the law in indigenous territories, that means that the labour undertaken by poorly paid employees and most frequently organised by unseen actors is by necessity clandestine, precarious, undocumented and, due to its geographical remoteness, ‘slave-like’ (underneath the Brazilian authorized definition). Though condemned by the Munduruku leaders, this exercise has been co-opting younger, indigenous males into capital-waged labour relations resulting in inner conflicts which might be a manifestation of the broader tensions between the safety and capitalisation of the forest assets.

A rise in logging concessions continues to be pushed as a device for forest conservation as a part of a broader perception in regulation by way of personal property; but indigenous teams have lengthy argued that efficient, statutory safety of their territorial borders is a ample assure of forest preservation. What they now face is the opposite: Federal courts are at the moment debating legal guidelines that might make authorized wildcat mining in indigenous territories by non-indigenous peoples (Invoice 1331/2022) and would for the primary time enable transnational company mining in these lands (Invoice 6050/2022). Moreover, the authority to demarcate indigenous lands could be transferred from authorities to a Nationwide Congress (PEC 59/2023) dominated by a pro-agribusiness foyer that has already acknowledged it will paralyse the demarcation of indigenous lands. The proof introduced right here is of a symbiotic moderately than conflictual relationship between illicit and ‘regularised’ extraction, whereby new ‘authorized’ infrastructures facilitate moderately than deal with the transgression of ostensibly protecting borders, with grave implications for the sovereignty and livelihoods of indigenous and conventional communities and the ecosystems of which they’re half.

The Amazon’s centrality to overlapping, converging and conflicting methods for carbon seize, carbon buying and selling, timber and mineral extraction at a world scale signifies that the regulatory challenges introduced listed here are additionally of a transboundary nature. Not solely are some 3,600 mining functions scattered throughout the basin, however the UK authorities is amongst these investing within the area underneath the premise that well-defined property rights will assist deal with illicit land grabs and invasion. This liberal market-based perception has already underpinned the UK’s partnership with Brazil to part some 1.3 million hectares of the globe’s most necessary biome to timber extraction, whereas planning an additional 5 million hectares by 2030.

The institutional enthusiasm and justification for these transborder methods and transactions depend on the continued imposition of a linear temporal framework and steeply hierarchical coverage agenda that determines to rework house and, importantly, social relations on the frontier. A logic that seeks to deliver into line these whose resistance has traditionally been translated as a barrier to progress is thus sustained by the developmentalist agenda for the Amazon. Though this can be accompanied by a discourse that departs from earlier colonial and navy intervals, the protests of the Munduruku that quickly shut down the Local weather Change Convention of Events (COP 30) in Brazil’s Amazon manifest that alternate visions, social and ecological relations persist inside their territorial borders that would present for social and political potentialities past them.

Rosamaria Loures is a doctoral candidate in Social Anthropology on the College of Brasília (UnB). She holds a grasp’s diploma in Environmental Sciences from the Federal College of Western Pará (UFOPA), and works as an advisor to the Munduruku Wakoborũn Girls’s Affiliation (since 2018) and the Munduruku Ipereğ Ayũ Motion (since 2012).

Brian Garvey is a researcher on the Division of Work, Employment and Organisation on the College of Strathclyde. His present analysis investigates native and world tensions associated to labour, land use and the commodification of pure assets. He’s a co-founder of the Centre for the Political Financial system of Labour.

Steven Owens is a researcher specialising in geospatial information for company accountability with a concentrate on provide chain transparency, working in collaboration with Indigenous communities.

Mauricio Torres holds a Masters and PhD in Human Geography from the College of São Paulo. He’s Professor on the Institute of Amazonian Agriculture (INEAF) and on the Federal College of Pará (UFPA), and Coordinator of the Decentralized Execution Settlement between the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples (MPI) and the Federal College of Pará (UFPA).

Deise Cristina Lima de Oliveira holds a level in Rural Improvement from the Federal College of Pará (UFPA) and is a grasp’s pupil within the Amazonian Agriculture Program at UFPA, the place she conducts analysis within the space of territorial conflicts and the rights of conventional peoples and communities. At the moment, she is a technical advisor to the Wakoborũn Affiliation and the Ipereg Ayũ Motion.

Ana Carolina Alfinito holds a legislation diploma from USP and a doctorate in political sociology from the Max Planck Institute for the Examine of Societies. She is at the moment a postdoctoral researcher on the Institute of Amazonian Agricultures of the Federal College of Pará (INEAF/UFPA) and a marketing consultant for the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples (MPI).

Hugo Gravina Affonso is a geographer and holds a PhD in Household Farming and Sustainable Improvement from the Federal College of Pará. He’s at the moment a postdoctoral researcher on the Institute of Amazonian Agriculture (INEAF/UFPA).

Bárbara Wanderley holds a bachelor’s diploma in Geography from the Federal College of Pernambuco (UFPE) and a grasp’s diploma in Geography from the Federal College of Paraná (UFPR). At the moment, she is a doctoral candidate in Philosophy on the College of Strathclyde, the place she is creating interdisciplinary analysis articulating philosophy and socioenvironmental conflicts.

Picture credit score: Mirna Wabi-Sabi by way of Unsplash